Turner Classic Movies concludes their John Ford tribute on Friday, July 31, 2020, with a showing of The Horse Soldiers and six other Ford films.

TCM has been airing a selection of Ford’s films every Friday in July, with 36 films in total to be aired.

Starting at 12 pm ET on Friday, July 24, 2020, TCM will broadcast these seven films, with The Horse Soldiers as the prime time film at 8 pm EST:

Starting at 12 pm ET on Friday, July 24, 2020, TCM will broadcast these seven films, with The Horse Soldiers as the prime time film at 8 pm EST:

You can find more information at: TCM John Ford Tribute

The schedule for the day is: TCM Schedule for July 31

Below is a trailer for The Horse Soldiers (1959).

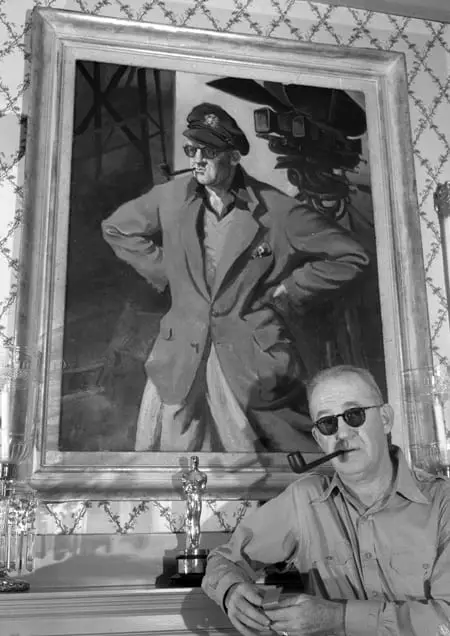

About John Ford (from Wikipedia)

John Ford (February 1, 1894 – August 31, 1973) was an American film director. He is renowned both for Westerns such as Stagecoach (1939), The Searchers (1956), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), as well as adaptations of classic 20th-century American novels such as The Grapes of Wrath (1940). His four Academy Awards for Best Director (in 1935, 1940, 1941, and 1952) remain a record. One of the films for which he won the award, How Green Was My Valley, also won Best Picture.

In a career of more than 50 years, Ford directed more than 140 films (although most of his silent films are now lost) and he is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers of his generation. Ford’s work was held in high regard by his colleagues, with Orson Welles and Ingmar Bergman among those who named him one of the greatest directors of all time.

Ford made frequent use of location shooting and long shots, in which his characters were framed against a vast, harsh, and rugged natural terrain.

Below is a tribute to Ford from TCM.

Talkies: 1928–1939

Ford was one of the pioneer directors of sound films. Ford’s output was fairly constant from 1928 to the start of World War II; he made five features in 1928 and then made either two or three films every year from 1929 to 1942, inclusive. Three films were released in 1929—Strong Boy, The Black Watch and Salute. His three films of 1930 were Men Without Women, Born Reckless and Up the River, which is notable as the debut film for both Spencer Tracy and Humphrey Bogart, who were both signed to Fox on Ford’s recommendation (but subsequently dropped). Ford’s films in 1931 were Seas Beneath, The Brat and Arrowsmith; the last-named, adapted from the Sinclair Lewis novel and starring Ronald Colman and Helen Hayes, marked Ford’s first Academy Awards recognition, with five nominations including Best Picture.

By 1940 he was acknowledged as one of the world’s foremost movie directors. His growing prestige was reflected in his remuneration—in 1920, when he moved to Fox, he was paid $300–600 per week. As his career took off in the mid-Twenties his annual income significantly increased. He earned nearly $134,000 in 1929, and made over $100,000 per annum every year from 1934 to 1941, earning a staggering $220,068 in 1938.

1939–1941

Stagecoach (1939) was Ford’s first western since 3 Bad Men in 1926, and it was his first with sound. Reputedly Orson Welles watched Stagecoach forty times in preparation for making Citizen Kane. It remains one of the most admired and imitated of all Hollywood movies, not least for its climactic stagecoach chase and the hair-raising horse-jumping scene, performed by the stuntman Yakima Canutt.

Production chief Walter Wanger urged Ford to hire Gary Cooper and Marlene Dietrich for the lead roles, but eventually accepted Ford’s decision to cast Claire Trevor as Dallas and a virtual unknown, his friend John Wayne, as Ringo.

Stagecoach is significant for several reasons—it exploded industry prejudices by becoming both a critical and commercial hit, grossing over US$1 million in its first year (against a budget of just under $400,000), and its success (along with the 1939 Westerns Destry Rides Again with Dietrich and Michael Curtiz’s Dodge City with Erroll Flynn) revitalized the moribund genre, showing that Westerns could be “intelligent, artful, great entertainment—and profitable”. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, and won two Oscars, for Best Supporting Actor (Thomas Mitchell) and Best Score. Stagecoach became the first in the series of seven classic Ford Westerns filmed on location in Monument Valley, with additional footage shot at another of Ford’s favorite filming locations, the Iverson Movie Ranch in Chatsworth, Calif. Ford skillfully blended Iverson and Monument Valley to create the movie’s iconic images of the American West.

John Wayne had good reason to be grateful for Ford’s support; Stagecoach provided the actor with the career breakthrough that elevated him to international stardom. Over 35 years Wayne appeared in 24 of Ford’s films and three television episodes. Ford is credited with playing a major role in shaping Wayne’s screen image. Cast member Louise Platt, in a letter recounting the experience of the film’s production, quoted Ford saying of Wayne’s future in film: “He’ll be the biggest star ever because he is the perfect ‘everyman.'”

Stagecoach marked the beginning of the most consistently successful phase of Ford’s career—in just two years between 1939 and 1941 he created a string of classics films that won numerous Academy Awards. Ford’s next film, the biopic Young Mr Lincoln (1939) starring Henry Fonda, was less successful than Stagecoach, attracting little critical attention and winning no awards. It was not a major box-office hit although it had a respectable domestic first-year gross of $750,000, but Ford scholar Tag Gallagher describes it as “a deeper, more multi-leveled work than Stagecoach … (which) seems in retrospect one of the finest prewar pictures”.

Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) was a lavish frontier drama co-starring Henry Fonda and Claudette Colbert; it was also Ford’s first movie in color and included uncredited script contributions by William Faulkner. It was a big box-office success, grossing $1.25 million in its first year in the US and earning Edna May Oliver a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination for her performance.

Despite its uncompromising humanist and political stance, Ford’s screen adaptation of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath was both a big box office hit and a major critical success, and it is still widely regarded as one of the best Hollywood films of the era. During production, Ford returned to the Iverson Movie Ranch to film a number of key shots, including the pivotal image depicting the migrant family’s first full view of the fertile farmland of California, which was represented by the San Fernando Valley as seen from the Iverson Ranch.

The Grapes of Wrath was followed by two less successful and lesser-known films. The Long Voyage Home (1940) was, like Stagecoach, made with Walter Wanger through United Artists. Adapted from four plays by Eugene O’Neill, it was scripted by Dudley Nichols and Ford, in consultation with O’Neill. Although not a significant box-office success (it grossed only $600,000 in its first year), it was critically praised and was nominated for seven Academy Awards—Best Picture, Best Screenplay, (Nichols), Best Music (Best Photography (Gregg Toland), Best Editing (Sherman Todd), Best Effects (Ray Binger & R.T. Layton), and Best Sound (Robert Parrish). It was one of Ford’s personal favorites; stills from it decorated his home and O’Neill also reportedly loved the film and screened it periodically.[38]

Ford’s last feature before America entered World War II was his screen adaptation of How Green Was My Valley (1941), starring Walter Pidgeon, Maureen O’Hara and Roddy McDowell in his career-making role as Huw.

How Green Was My Valley became one of the biggest films of 1941. It was nominated for ten Academy Awards and was a huge hit with audiences, coming in behind Sergeant York as the second-highest-grossing film of the year in the US and taking almost $3 million against its sizable budget of $1,250,000. Ford was also named Best Director by the New York Film Critics, and this was one of the few awards of his career that he collected in person (he generally shunned the Oscar ceremony).

War years

During World War II, Ford served as head of the photographic unit for the Office of Strategic Services and made documentaries for the Navy Department. Ford filmed the Japanese attack on Midway from the power plant of Sand Island and was wounded in the arm.

Ford was also present on Omaha Beach on D-Day. He crossed the English Channel on the USS Plunkett (DD-431), which anchored off Omaha Beach at 0600.

His last wartime film was They Were Expendable (MGM, 1945), an account of America’s disastrous defeat in The Philippines, told from the viewpoint of a PT boat squadron and its commander.

Post-war career

Ford directed sixteen features and several documentaries in the decade between 1946 and 1956. As with his pre-war career, his films alternated between (relative) box office flops and major successes, but most of his later films made a solid profit, and Fort Apache, The Quiet Man, Mogambo and The Searchers all ranked in the Top 20 box-office hits of their respective years.

Ford’s first postwar movie My Darling Clementine (Fox, 1946) was a romanticized retelling of the primal Western legend of Wyatt Earp and the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, with exterior sequences filmed on location in the visually spectacular (but geographically inappropriate) Monument Valley. It reunited Ford with Henry Fonda (as Earp) and co-starred Victor Mature in one of his best roles as the consumptive, Shakespeare-loving Doc Holliday, with Ward Bond and Tim Holt as the Earp brothers.

Fort Apache (Argosy/RKO, 1948) was the first part of Ford’s so-called ‘Cavalry Trilogy’, all of which were based on stories by James Warner Bellah. It featured many of his ‘Stock Company’ of actors, including John Wayne, Henry Fonda, Ward Bond, Victor McLaglen, Mae Marsh, Francis Ford (as a bartender), Frank Baker, Ben Johnson and also featured Shirley Temple.

Fort Apache was followed by another Western, 3 Godfathers, a remake of a 1916 silent film starring Harry Carey (to whom Ford’s version was dedicated), which Ford had himself already remade in 1919 as Marked Men, also with Carey and thought lost. It starred John Wayne, Pedro Armendáriz and Harry “Dobe” Carey Jr (in one of his first major roles) as three outlaws who rescue a baby after his mother (Mildred Natwick) dies giving birth, with Ward Bond as the sheriff pursuing them.

In 1949, Ford completed film the second installment of his Cavalry Trilogy, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (Argosy/RKO, 1949), starring John Wayne and Joanne Dru, with Victor McLaglen, John Agar, Ben Johnson, Mildred Natwick and Harry Carey Jr. Again filmed on location in Monument Valley, it was widely acclaimed for its stunning Technicolor cinematography,

1950s

Rio Grande (Republic, 1950), the third part of the ‘Cavalry Trilogy’, co-starred John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara.

This was followed in 1952 with a resounding success, The Quiet Man (Republic, 1952), a pet project which Ford had wanted to make since the 1930s. It became his biggest grossing picture to date, taking nearly $4 million in the US alone in its first year and ranking in the top 10 box office films of its year. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won Ford his fourth Oscar for Best Director.

In 1955, Ford was hired by Warner Bros to direct the Naval comedy Mister Roberts, starring Henry Fonda, Jack Lemmon, William Powell, and James Cagney, but there was conflict between Ford and Fonda, who had been playing the lead role on Broadway for the past seven years and had misgivings about Ford’s direction. During a three-way meeting with producer Leland Hayward to try and iron out the problems, Ford became enraged and punched Fonda on the jaw, knocking him across the room, an action that created a lasting rift between them.

After the incident Ford became increasingly morose, drinking heavily and eventually retreating to his yacht, the Araner, and refusing to eat or see anyone. Production was shut down for five days and Ford sobered up, but soon after he suffered a ruptured gallbladder, necessitating emergency surgery, and he was replaced by Mervyn LeRoy.

The Searchers (1956)

Ford returned to the big screen with The Searchers (Warner Bros, 1956), the only Western he made between 1950 and 1959, which is now widely regarded as not only one of his best films, but also by many as one of the greatest westerns, and one of the best performances of John Wayne’s career. Shot on location in Monument Valley, it tells of the embittered Civil War veteran Ethan Edwards who spends years tracking down his niece, kidnapped by Comanches as a young girl. The supporting cast included Jeffrey Hunter, Ward Bond, Vera Miles and rising star Natalie Wood.

It was very successful upon its first release and became one of the top 20 films of the year, grossing $4.45 million, although it received no Academy Award nominations. However, its reputation has grown greatly over the intervening years—it was named the Greatest Western of all time by the American Film Institute in 2008 and also placed 12th on the Institute’s 2007 list of the Top 100 greatest movies of all time.

The Wings of Eagles (MGM, 1957) was a fictionalized biography of Ford’s old friend, aviator-turned-scriptwriter Frank “Spig” Wead, who had scripted several of Ford’s early sound films. It starred John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara, with Ward Bond as John Dodge (a character based on Ford himself).

The Last Hurrah, (Columbia, 1958), set in present-day of the 1950s, starred Spencer Tracy, who had made his first film appearance in Ford’s Up The River in 1930. Tracy plays an aging politician fighting his last campaign, with Jeffrey Hunter as his nephew. Katharine Hepburn reportedly facilitated a rapprochement between the two men, ending a long-running feud, and she convinced Tracy to take the lead role, which had originally been offered to Orson Welles (but was turned down by Welles’ agent without his knowledge, much to his chagrin). It did considerably better business than either of Ford’s two preceding films, grossing $950,000 in its first year.

In 1959 Ford filmed The Horse Soldiers (Mirisch Company-United Artists, 1959), a Civil War story starring John Wayne and William Holden. Although Ford professed unhappiness with the project, it was a commercial success, ranking in the year’s Top 20 box-office hits, grossing $3.6 million in its first year, and earning Ford his highest-ever fee—$375,000, plus 10% of the gross.

Last years, 1960–1973

Sergeant Rutledge (Ford Productions-Warner Bros, 1960) was Ford’s last cavalry film. Set in the 1880s, it tells the story of an African-American cavalryman (played by Woody Strode) who is wrongfully accused of raping and murdering a white girl.

Two Rode Together (Ford Productions-Columbia, 1961) co-starred James Stewart and Richard Widmark, with Shirley Jones and Stock Company regulars Andy Devine, Henry Brandon, Harry Carey Jr, Anna Lee, Woody Strode, Mae Marsh and Frank Baker, with an early screen appearance by Linda Cristal, who went on to star in the Western TV series The High Chaparral. It was a fair commercial success, grossing $1.6m in its first year.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (Ford Productions-Paramount, 1962) is frequently cited as the last great film of Ford’s career. It co-starred John Wayne and James Stewart, with Vera Miles, Edmond O’Brien, Andy Devine as the inept marshal Appleyard, Denver Pyle, John Carradine, and Lee Marvin in one of his first major roles as the brutal Valance, with Lee Van Cleef and Strother Martin as his henchmen. It is also notable as the film in which Wayne first used his trademark phrase “Pilgrim” (his nickname for James Stewart’s character).

According to Lee Marvin in a filmed interview, Ford had fought hard to shoot the film in black-and-white to accentuate his use of shadows. Still, it was one of Ford’s most expensive films at US$3.2 million.

After completing Liberty Valance, Ford was hired to direct the Civil War section of MGM’s epic How The West Was Won, the first non-documentary film to use the Cinerama wide-screen process. Ford’s segment featured George Peppard, with Andy Devine, Russ Tamblyn, Harry Morgan as Ulysses S. Grant, and John Wayne as William Tecumseh Sherman.

Donovan’s Reef (Paramount, 1963) was Ford’s last film with John Wayne. Filmed on location on the Hawaiian island of Kauai (doubling for a fictional island in French Polynesia), it was a morality play disguised as an action-comedy, which subtly but sharply engaged with issues of racial bigotry, corporate connivance, greed and American beliefs of societal superiority. The supporting cast included Lee Marvin, Elizabeth Allen, Jack Warden, Dorothy Lamour, and Cesar Romero. It was also Ford’s last commercial success, grossing $3.3 million against a budget of $2.6 million.

Cheyenne Autumn (Warner Bros, 1964) was Ford’s epic farewell to the West, which he publicly declared to be an elegy to the Native American. It was his last Western, his longest film and the most expensive movie of his career ($4.2 million), but it failed to recoup its costs at the box office and lost about $1 million on its first release. The all-star cast was headed by Richard Widmark, with Carroll Baker, Karl Malden, Dolores del Río, Ricardo Montalbán, Gilbert Roland, Sal Mineo, James Stewart as Wyatt Earp, Arthur Kennedy as Doc Holliday, Edward G. Robinson, Patrick Wayne, Elizabeth Allen, Mike Mazurki and many of Ford’s faithful Stock Company, including John Carradine, Ken Curtis, Willis Bouchey, James Flavin, Danny Borzage, Harry Carey Jr., Chuck Hayward, Ben Johnson, Mae Marsh and Denver Pyle.

Ford’s last completed feature film was 7 Women (MGM, 1966), a drama set in about 1935, about missionary women in China trying to protect themselves from the advances of a barbaric Mongolian warlord. Anne Bancroft took over the lead role from Patricia Neal, who suffered a near-fatal stroke two days into shooting. Unfortunately, it was a commercial flop, grossing only about half of its $2.3 million budget.

Ford’s health deteriorated rapidly in the early 1970s; he suffered a broken hip in 1970 which put him in a wheelchair. He had to move from his Bel Air home to a single-level house in Palm Desert, California, near Eisenhower Medical Center, where he was being treated for stomach cancer. The Screen Directors Guild staged a tribute to Ford in October 1972, and in March 1973 the American Film Institute honored him with its first Lifetime Achievement Award at a ceremony which was telecast nationwide, with President Richard Nixon promoting Ford to full Admiral and presenting him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Ford died on 31 August 1973 at Palm Desert and his funeral was held on 5 September at Hollywood’s Church of the Blessed Sacrament.

Ford On The Set

Ford was legendary for his discipline and efficiency on-set and was notorious for being extremely tough on his actors, frequently mocking, yelling and bullying them; he was also infamous for his sometimes sadistic practical jokes. Any actor foolish enough to demand star treatment would receive the full force of his relentless scorn and sarcasm. He once referred to John Wayne as a “big idiot” and even punched Henry Fonda. Henry Brandon (who played Chief Scar from The Searchers) once referred to Ford as “the only man who could make John Wayne cry”.

More about John Ford

John Ford film schedule on TV Guide

John Ford’s birthday: February 1, 1894

Recent Comments